The challenges of a rates cap

Increasing rates is a hot topic at present, with government agreeing to progress a rates cap as part of local government reform in 2026.

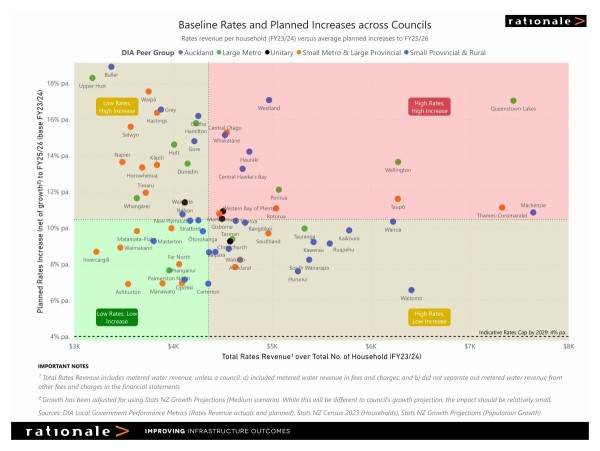

Minister for Local Government, Hon Simon Watts has indicated a rates cap of 4% per annum.

The cap will apply to all sources of rates – general rates, targeted rates and uniform annual charges – but will exclude water charges and other non-rates revenue like fees and charges.

Councils will not be able to increase rates beyond the upper end of the range, unless they have permission from a regulator appointed by central government. Permission will only be granted in extreme circumstances, such as a natural disaster, and councils will need to show how they will return to the target range.

At the same time, The Infrastructure Commission has estimated that New Zealand has a total current and future infrastructure deficit of $209 billion. So, we are already well behind on infrastructure investment. It becomes challenging to see how the country will be able to overcome this deficit with a cap on rates.

We’re always interested to see what the data looks like behind the political rhetoric (particularly in an election year).

We have taken data provided by Central Govt and used it to get a national view of what planned rates increases are like between councils across NZ. The data sources we’ve used include:

- DIA Local Government Performance Metrics (Rates Revenue actuals and planned)

- Stats NZ Census 2023 (Households)

- Stats NZ Growth Projections (Population Growth)

Click here to see a larger image.

Before we get into it, it’s important that this is a high-level comparison, based on standardised financial data – there will be differences between what’s seen here and the specifics that councils have to hand. It also doesn’t strip out water rates (other than Auckland). However, water costs will still need to be paid by ratepayers, regardless of the entity collecting the money, so the net result for ratepayers is roughly the same.

It also doesn’t dive into the intricacies of specific councils’ funding and rating arrangements, of which there are many. A good example of this is Mackenzie District Council, which receives significant rates from the power generators located in their district, which makes the cost per household seem higher than it actually is (by roughly $1,500 a year).

So, with that said, let’s dive into it. While there are a number of ‘hot takes’ you can take out of the above information, we think there are three interesting issues that this raises.

1. All councils are already planning rates increases well above the proposed cap

Every council currently sits above the 4% pa. indicative cap, with the average sitting at 11% pa. increases through to FY25/26, regardless of whether their current rates base is low or high.

This suggests the proposed cap is not marginal, it represents a material constraint on existing financial strategies – it isn’t just a future guardrail. If introduced without offsetting funding tools, councils would need to either materially reduce planned infrastructure spend or reprofile it sharply. This will be a considerable challenge for many councils and risks exacerbating the current infrastructure deficit and kicking the can down the road for future generations, who will need to pick up the bill.

2. Low-rates councils are often planning the highest increases

There are a high number of councils in the ‘low rates, high increase’ quadrant, including several provincial and growth councils, implying a situation of catch up, not excessive spending.

This pattern suggests that high planned increases are often needed due to structural catch-up because of historical underinvestment, growth pressures and inflation, rather than discretionary spending on ‘nice to haves’. A uniform rates cap risks locking in historic underfunding, particularly for councils now trying to lift renewals and growth-enabling infrastructure.

3. Councils with already high rates per household are also planning increases well over 4%

Councils with already high rates per household aren’t clustered near the proposed 4% cap. Many are instead planning 8–12%+ average annual increases through to FY25/26.

A common political framing is that a rates cap primarily disciplines councils that have ‘let rates get too high. However the above chart suggests that high rates do not imply financial comfort, instead high planned increases are being driven by cost and asset pressures, not discretionary expansion.

Councils charging more today are often doing so because their cost base and asset challenges are structurally higher, not because they have excess fiscal headroom. They’re facing a range of challenges including high population growth, high visitor numbers, aging infrastructure and low ratepayer numbers.

The debate on rates capping is often framed as a question of discipline and affordability. As always, the data tells a more complex story (which is why we love it). The reality is many councils are already stretching to fund essential infrastructure, not shiny new projects. A blunt cap, without accompanying reform, risks exacerbating the existing infrastructure deficit for political points today, making this worse for future ratepayers.

Understanding those trade-offs requires more than rhetoric and point scoring for votes, it requires data, context, and a system-wide view.

Rationale helps councils and decision-makers cut through the noise and make informed choices about infrastructure investment under changing policy settings. For more information, visit rationale.co.nz or get in touch with our team.

BACK